Hong Kong: If I take a bullet for you would you go on a strike for me?

The 2019 Hong Kong protests are a series of demonstrations, taking place in Hong Kong during the spring, summer and autumn of this year. An Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill between China, Taiwan and Hong Kong, initiated the current strings of protest. What started as a protest against a single bill has turned into a fight for five key demands that the Hong Kong public is requesting from The People’s Republic of China: (1) Full withdrawal of the extradition bill, (2) A commission of inquiry into alleged police brutality, (3) Retracting the classification of protesters as “rioters”, (4) Amnesty for arrested protesters and (5) Dual universal suffrage, meaning for both the Legislative Council and the Chief Executive. These are the demands presented by Hongkongers, but ultimately the protests have turned into a greater fight for independent sovereignty from China (henceforth Mainland) especially as Hong Kong is to be handed over to The People’s Republic of China in 2047 as part of the deal struck with the British, marking the end of “one country, two systems”. Our intern at The Danish Foreign Policy Society recounts her recent trip to Hong Kong in October.

Friday the 4th of October was my third day in Hong Kong. Despite the clear sunny day and a low amount of pollution, there was tension in the air. This can be said about any number of days before a protest was about to break out, but on this particular day the tension was nerving. I had seen smaller protests every day, yet on this Friday there was an inexplainable heaviness in the air. Except for the odd poster or graffiti exclaiming distaste for China, there was no visual indication of the long row of serial demonstrations that have taken place so far. Families, locals, expats and tourists were out enjoying their day without disturbance. The streets were buzzing, and the people seemed carefree. Nonetheless, as I was about to learn, Hongkongers are capable of going from peaceful to protesting surroundings to strong protests in the span of a few minutes. When they need to, they continue their daily routine, but they can also very easily switch and become passionate demonstrators in the streets. In this way they are very adaptable.

On my first night in Hong Kong, I met two young men, one from Kazakhstan and one from Turkey. As they were not Hongkongers they didn’t contribute to the protests, but they were still affected on a daily basis by the demonstrations. However, these disturbances were often minor inconveniences such as the disruption of their plans because their friends were out demonstrating, or due to the transportation services being cancelled. The two men have come to Hong Kong for work and have been here for five years. “Hong Kong, to a certain extent feels like a free country. Here I have more job opportunities and more chances of a better life which I cannot achieve back home “the young man from Kazakhstan told me. “But because I look completely Chinese, I fear as a Muslim that I can no longer live according to my lifestyle if Mainland were to completely takeover.” They have both lived in Mainland before and prefer Hong Kong due to the larger international presence. They feel that the Hongkongers are doing what they have to, and the outcome of the protests would not only dictate the future of Hongkongers but also theirs.

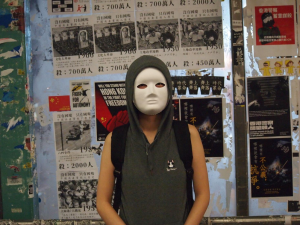

My accommodation was in Causeway Bay on Hong Kong Island. A hotspot for the protests due to Victoria Park. That particular Friday afternoon, the streets were quickly filling up with protestors– it was the end of a long workweek. As transportation was already starting to shut down, I was forced to walk west bound. I went through a footbridge where an older man in his 70s or 80s was putting up anti-mainland flyers. “I’m a weak old man, and I can’t participate in the long protests. I can help by nailing flyers to the wall and handing out posters. I might be old, but I still want to fight for the newer generations” he told me with his limited English. “Please let the world know that we are being threatened”. A phrase I have heard many times during my stay in Hong Kong. On the same footbridge a young woman in her twenties was restlessly pacing up and down the footbridge wearing a white mask that resembles the one from Phantom of The Opera. We struck up a conversation, and her anger was apparent. She said: “It’s going to be war tonight.” She told me that this particular protest was important because of the Anti-Mask Law, which had been passed by the government was to be enforced at midnight. The people were furious because it meant that the anonymity of the protesters would be gone. “We won’t allow Carrie Lam (Chief executive of Hong Kong) government to set us up like this. Without our anonymity China will win. Our anonymity is what keeps us safe from Chinese control. In Hong Kong we have the right to be anonymous – a right they don’t have in Mainland. Masks are not only for protesting. Some people use it for medical reasons. Why should they suffer?”For the rest of my trip I constantly saw people wearing masks even though the ban had been enforced. I even heard a rumor that the Islamic community in Hong Kong received an unusual amount of people convert to the religion as face-coverage is allowed for religious purposes.

I met up with a friend, who is a native Mainlander (who shall remain anonymous) to get her perspective. She has spent her whole life in China up until her master’s studies. She accepted a job in Hong Kong, after having spent a few years in France. It has been a hard transition for her. She has felt more isolated from young Hongkongers than from the older ones. She says that she experiences discrimination on a weekly basis due to her background. Sometimes people would flat-out ignore her when they hear her dialect. Even her visa process took unnecessarily long time to process. Due to the uprisings she is looking to return to Europe, since Hong Kong has let her down. “I don’t understand why we (Mainland Chinese) are seen as the villain at all times. The Hongkongers are creating havoc and are violent and sometimes I feel unsafe.” We had a long conversation about what it means to be a Chinese person living abroad. She told me several times that everybody thinks she is brainwashed by the Chinese government. Especially Hongkongers subscribe to this stereotype. As she has lived outside of China the past five years, she is very aware of the manipulation of information and censorship from the Communist Party. “The quality of life here in Hong Kong is worse than most places in Mainland.” For her it simply makes sense that Hong Kong is a part of China.

On Friday, after spending the evening in parts of Hong Kong Island where there was no sign of demonstrations except for some closed stores and no transportation, I had to walk home. As I progressed further towards Causeway Bay, I could see the signs of a protest. Face masks, graffiti, broken bottles, flyers and umbrellas on the street. Yet it was eerily quiet and empty. The calm before the storm. You could feel the phantom presence of the protesters. The closer I got to Causeway Bay the louder the singing and roaring of the crowd became. I managed to take a bus closer to Causeway Bay. As I got off the bus, I was met by a huge crowd all wearing black and masks and holding an umbrella. They were standing and waiting for something to happen. As of that moment, I had no idea what it could be. They chanted songs and shouted rallying cries. As the night progressed the crowd became bigger. As did the group of people wearing gas masks and neon-green vests with JOURNALIST written on them. For some time the situation was calm, while a white statue called Lady Liberty was revealed. Lady Liberty is a female protester holding an umbrella and a flag and wearing a gasmask. Afterwards the sound of rallying cries commenced at the same time as banks and stores linked to Mainland were destroyed and vandalised. Fire trucks went back and forth to extinguish store alarms and fires. In the beginning there were lots of tourists and families watching. As the demonstration continued those groups disappeared and the cries and songs of the protesters moved further west while Lady Liberty was loaded on a truck and escorted away.

“I mean it’s surprising and heart-warming to see how Hongkongers are so selfless and united in bad times. That definitely was not how I perceived us all these years. I’ve always known Hong Kong people being shy (some would say cold) on the outside but inside they are very kind and helpful”. These words were spoken by a friend who shall remain anonymous except for the fact that she is a native Hongkonger in her mid-twenties. It’s too risky for her to protest since her family will get in trouble if she’s caught, because they work in the public-sector. She told me about the evolution of Mainland presence in Hong Kong especially in the police during the past year. “Physically they didn’t look Cantonese. And those who did spoke with a Hokkien accent (A Chinese dialect).” She told me that they acted differently – they were more aggressive. The young protestors are often prepared, thanks to the local police officers, who are leaking information to them. Mainland Chinese presence is discussed daily between her and her friends. The number of Mainlanders that have moved to Hong Kong within the last few years has been a big shock to them. From businesses to civilians. They feel like Mainlanders are given easier access to housing, studies etc., whereas the Hongkongers have to fight for these things. For her, it isn’t just about the five demands. It is about her future and she believes that her future does not belong to China. As she told me, Hong Kong can already be difficult to navigate when you’re part of the middle-class due to the fierce competition in school, the lack of affordable housing and an uncertain future where it can be hard to juggle a work-life balance. Her whole life she has felt that Hongkongers just didn’t care about their situation, that people seemed disinterested. “In the past Hong Kong people were quite apolitical. So, in the beginning nobody saw this tenacity coming at all. But apparently it is in our bones. I’ve witnessed the people grow into very loving and gentle beings, especially towards strangers in a matter of months.” As an only child, her parents are worried about her future. In her social circle many families are split because of this matter. Her mother agrees fully with the demonstrations, but for her father it’s a different story. He cares more about instant peace, and he prefers to remain neutral to the matter. “He’s not really capable of dealing with noise and any other manifestations of it. He tends to want to restore peace in the most superficial way. He has a way of only seeing the downside of the methods of the protestors. This makes it difficult for him to be constructive.”. However, she believes that it’s her generation that will take up the fight. Many of her friends have been beaten up by the police, which have left some of them quite startled in the period after. “The white terror is real,” she told me several times. She is referring to the political persecution of individuals fighting for a pro-democracy movement. She and her friends are counting on the international community for solidarity: “If I take bullets for you would you go on a strike for me?” those are her words for the rest of the world.

On Friday night as the truck loaded Lady Liberty and took off, the crowd quickly moved towards Central. The crowd which consisted mostly of young people, even teenagers, were off as quickly as they came. As I found myself ready to go home, it dawned on me that there were practically no civilians left on the street. In the direction of my home, I could see an enormous group of people wearing green with black helmets and shields. The Hong Kong Police were on their way towards the protesters. As I had the thought to turn right at the next corner and avoid them, I saw through a tiny alleyway on the right that the police were moving there as well but were moving much more quietly. I had no choice but to move left quickly. When my husband and I crossed the road, I heard some words being spoken in Cantonese through a megaphone and shots of grenades were shot at me and my husband. We ran as fast as we could towards the left and hid in a small alleyway with locals until we knew they had passed. Continuing towards the demonstrators who were waiting for them. Why they shot at me and my partner, I don’t know. Perhaps we looked like locals from afar or perhaps we just looked like a threat. Behind the main streets, restaurants were open, people were walking around normally and calmly only 5 min. away from the police. Throughout the night, I could see fighting from my windows. Instagram and Reddit were constantly updated with the fight between protestors and the police. This continued for the rest of my trip. I saw protests on a daily basis, with the next big one, on Sunday October 6. I tried to avoid the protests by spending the day in Kowloon, the part of Hong Kong that is physically attached to the Shenzhen province in China. But because transportation was cut off, there were protests both on Hong Kong Island and Kowloon. Nathan’s Road, a main road in Kowloon, was filled with demonstrators in the pouring rain. They joined hands, as a symbol of peace, through the majority of the road. They also acted as a supply chain, distributing scissors, posters and other tools for protest. I was told by civilians that I had to move away quickly because the police were on their way. As I was leaving, I saw them approaching, and for the first time since my arrival, I saw the police carrying firearms.

The impression of Hongkongers being impassive was not something I only heard from my friend. An elderly woman with a strong British accent told me the exact same thing a few days later in Wan Chai station. She was handing out a pro Hong Kong newspaper called Hong Kong Free Press, which is an online newspaper which has been printed for physical copies. She claims that this newspaper is free of “Beijing meddling”. She has the exact same sentiment as my friend had expressed, despite their large age difference. She has always felt that Hongkongers were indifferent to their situation. “I prefer neither a British rule nor a Beijing rule. I’m fighting for Chinese people from both Hong Kong and the Mainland to be free of persecution based on religion, ethnicity or political opinions.” She told me that her generation was a lost cause. She is fighting for the young generation as this is their fight and it’s her responsibility to aid them. She was very adamant that both Hong Kong and Mainland are prisoners of the Communist Party. But because Hong Kong has the knowledge of freedom; it is their responsibility to first free themselves and thereafter Mainlanders.

The Hongkongers I spoke to always used the same term to describe The People’s Republic of China – Beijing. For them Beijing is synonyms to Mainland China, The Communist Party, and their growing power since they were given back to China by the British in 1997. Beijing is far away, geographically and symbolically, which manifests itself through a strong feeling of dichotomy; an ‘Us vs. them’ mentality. Hongkongers like to see themselves as the good part of that equation with the ‘correct’ values such as freedom of speech, of the press and of assembly. As the old man in the footbridge told me: “once you have given someone something, it’s hard to take it back.” He is referring to the British giving Hong Kong semi-autonomy and certain values. By giving Hong Kong semi-autonomous status, China can’t expect them to reintegrate without conflict. However, that strong feeling of ‘us vs. them’ also exists on the other side. As evidenced by my friend from Mainland China who also feels detached from Hongkongers and their fight to resist a life she has been brought up in.

As I understood it from the locals that I spoke with, the five key demands symbolise a fight for keeping the rights that they already have and to defend those rights against The People’s Republic of China. Yet it’s slowly turning into a larger fight that questions the whole idea of the “one country, two systems” that will become “one country, one system” in 28 years. The youth seem set against accepting the terms of re-entering China after 156 years of separation. They have a strong sense of Hong Kong (and Cantonese) society, culture, people and values which for them are distinctly different than the China that has been formed by The Communist Party. The fight to eradicate China has already started.

Written by Meriem-Hadia Charif

Photo: © Zakaria Kheddam